The first few pages of Michael Friedel’s “Maldives Discovered – The Dawn of Maldives Tourism” immediately paint a tranquil picture of our island nation, a seemingly untouched “string of pearls” splashed across the Indian Ocean.

The renowned German photojournalist’s bird’s-eye view photographs — beautifully republished in this hardcover photo essay of some of his most iconic work — were the first images of the Maldives to be published worldwide back in 1974.

For much of the world it was their first time seeing, and hearing about, the Maldives. As for our parents and grandparents, it was their first time seeing how their islands look from the sky above.

Born in 1935, Friedel started working as a photographer and a photojournalist as a young student. His photos quickly started being published in leading titles in Germany, including Stern magazine and Der Spiegel newspaper. His visits to the Maldives starting in the seventies allowed him to experience and capture local tourism as it grew from its infancy to its current state as a multibillion-dollar industry.

His pictures of Ihuru and Vabbinfaru islands would go on to be featured in Stern magazine as the aforementioned first images of the Maldives, causing a sensation worldwide and ensuring Friedel’s own place in the history of Maldivian tourism.

As a young girl, I remember a singular runway next to the main building of the airport terminal. It has since expanded and developed to include multiple runways, but even the simple airport of the nineties that I remember is a far cry from the squat white building and lone airstrip as captured by Friedel. The photos seem strangely anachronistic in full colour yet are dated from1981 — a jarring reminder of how quickly the country’s development accelerated with the advent of tourism.

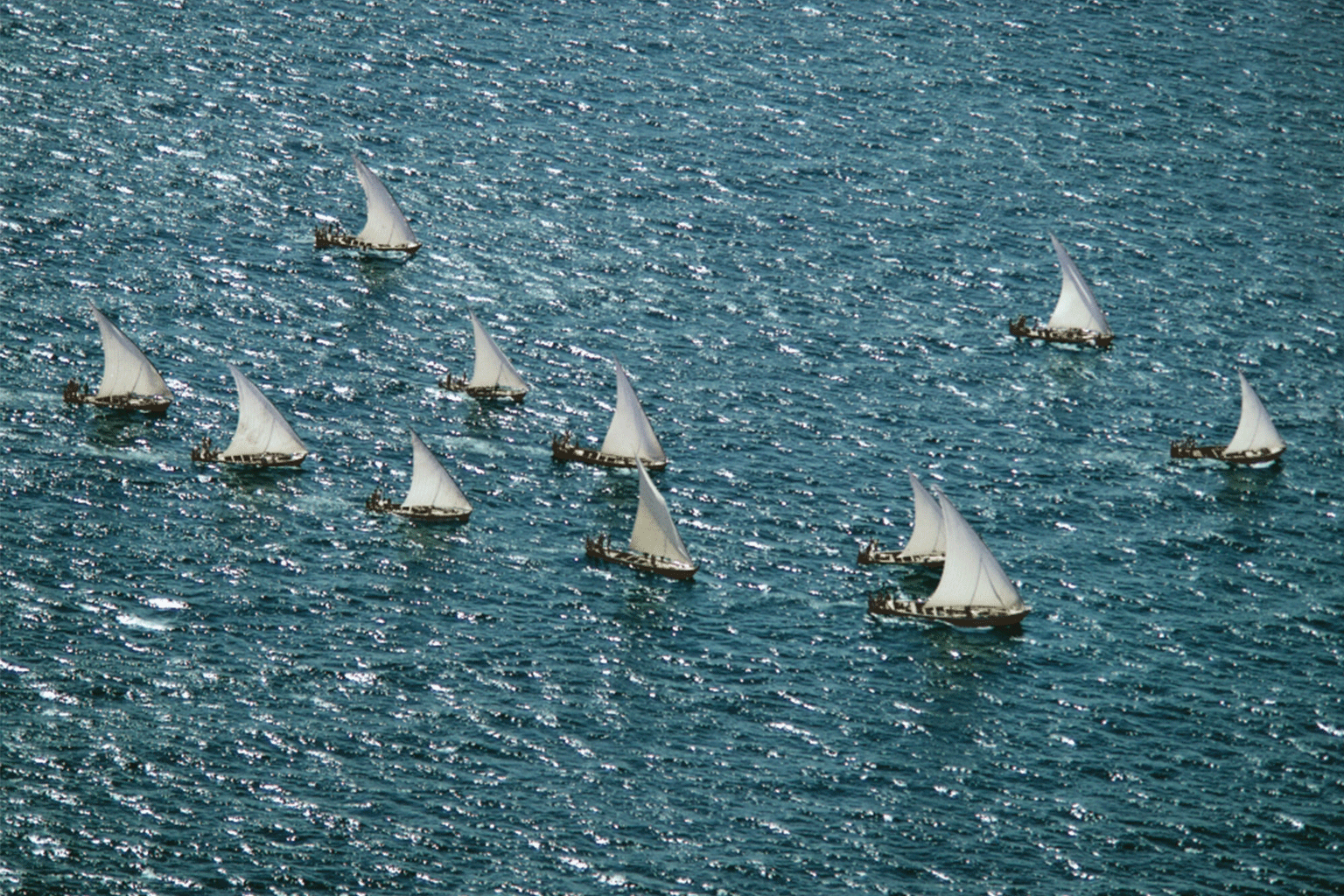

Then there are sights our generation never got to see and will most likely never see in our lifetime. Friedel’s images of sail boats, dhoni, are particularly noteworthy. Though sail boats have become an icon of the Maldives and a commonly featured motif in local souvenirs and artwork, only a handful are in limited use today. Friedel’s photo of not one but multiple dhoni sailing together across the sea is inconceivable in 21 st century Maldives.

The topic of dhoni cannot be discussed without at least a cursory recognition of the significance of fishing in the Maldives. Only relatively recently supplanted by tourism as the main economic industry of the country, Friedel’s images remind us that fishing will always be an integral part of the Maldivian identity.

The photos capture the often-harsh conditions faced by local fishermen, whether it’s long hours under the unforgiving equatorial sun or the physically demanding work of pole and line fishing.

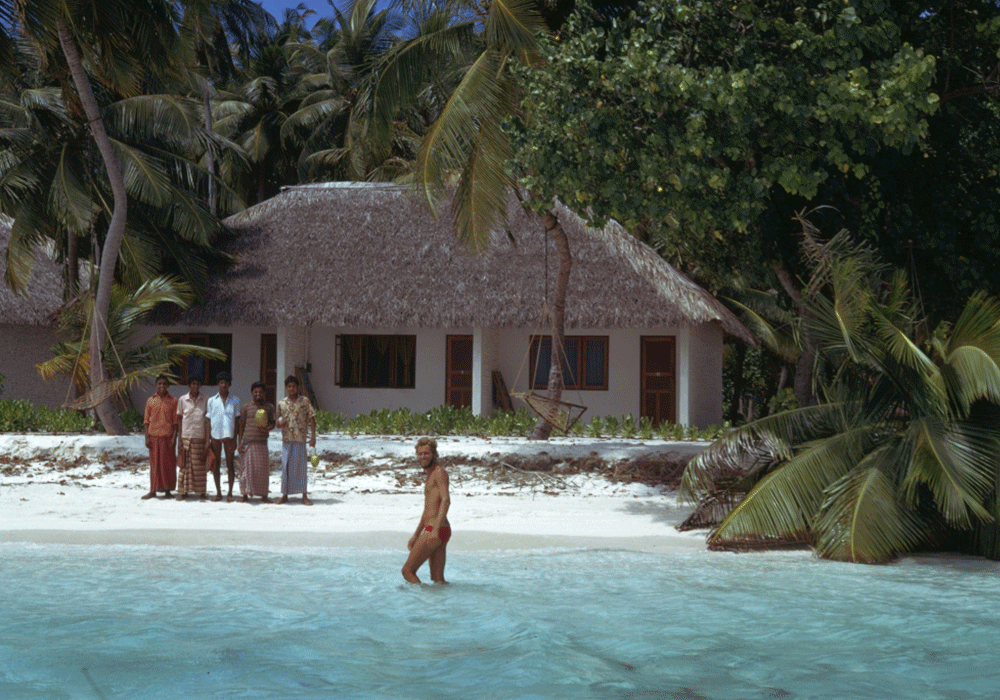

This first half of the book about the culture of the Maldives sets the stage for the latter portion introducing the early days of tourism. Many early tourists stayed on uninhabited islands with little to offer in the way of shelter or facilities. With the opening of the first official resort in 1972, guests could expect simple yet comfortable accommodations, tropical cuisines, and unpretentious service. Yet, the natural beauty of the country with its pristine beaches, sparkling oceans, and stunning sunsets were always the real attractions.

The last few pages of the collection cover the underwater world of the Maldives, with photos from Friedel’s snorkelling and diving adventures. Dolphins, sharks, feisty schools of fish, and colourful corals are only a glimpse of what the seas have to offer. The book does also acknowledge that the practice of feeding and touching underwater life as seen in some photos is now strictly forbidden.

“Maldives Discovered” is like opening a time capsule, capturing much of the Maldives during the early days of tourism. It also serves as a reminder of what will always be the true wealth of this country – its natural beauty.

Credits: All photos; Michael Friedel